The Other Side of 110

from THE GLOBE AND MAIL, Feb 20, 2019.

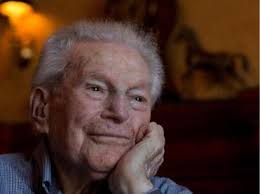

Like pretty much everyone of extraordinarily advanced age, Dr. Robert Wiener was continually peppered with one question: “What’s your secret?” He preferred to show a visitor rather than tell them. After cordial small-talk about politics and hockey, he slipped into his workout togs and, moving his dumbbells out of the way, hopped on the CCM stationary bicycle that sat next to the window in his top-floor residence overlooking Montreal. And then, with St. Joseph’s Basilica looming below, he demo’d his daily regimen: fifteen minutes fast, then fifteen minutes with the tension cranked up, until he was sweating.

The retired oral surgeon, who died on February 17, was Canada’s only male supercentenarian, a term reserved for people who are at least 110 years old. A highlight of his 55-year career was founding the dental clinic at the Jewish General Hospital for those of limited means. When he graduated from McGill University’s dental school, most people were still brushing their teeth with short pieces of bone fitted with pig bristles or badger hair; the first modern nylon-bristle toothbrush wouldn’t go on sale until two years later, in 1938.

According to the UCLA-based Gerontology Research Group, which tracks and verifies supercentenarians, Dr. Wiener is considered the oldest man ever to be born and die in Canada. There are thought to be between 600 and 1,000 supercentenarians in the world, the overwhelming majority of them women. Dr. Wiener, at 110 years and 113 days, was believed to be the 18th-oldest man on Earth.

Dr. Wiener was fastidious about his healthy habits, including a Mediterranean diet, regular exercise, a cultivated optimism and two squares of dark chocolate a day. His daily perusal of The Montreal Gazette and numerous health journals he subscribed to online may also have been medicine, although he mostly did it for fun.

Robert Manuel Wiener was born in Montreal on Oct. 27, 1908. The youngest of seven siblings (“I was the one who always had to run the errands,” he once told The Canadian Jewish News), he grew up in the Mile End neighbourhood – Mordecai Richler’s stomping ground – an ethnically rich area of fruit sellers and outdoor staircases where his parents, Louis and Anna, immigrants from Poland and Russia, respectively, had settled after moving from Amsterdam, where they met.

In grade school, he and his classmates knit towels for the soldiers in the trenches – of the First World War.

With no mass media as a diversion – commercial radio didn’t arrive until he was 12 – there were a lot of pick-up games of almost every sport. Street hockey was interrupted not with shouts of “Car!” but “Horse!” (A hockey fanatic, Dr. Wiener remembered rising from his seat in the old Mount Royal Arena, then home of his beloved Habs, to watch speedy Howie Morenz take the puck end-to-end himself – a testament to both the centreman’s skill and the fact the NHL didn’t allow forward passing in all zones until 1929.)

He was 13 when Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid opened at a cinema on St. Catherine Street and in his 20s when women became “persons” under the law in Canada.

He followed his older brother Judah into dentistry and his career in oral surgery included teaching dentistry at McGill for 25 years.

One measure of the spread of Dr. Wiener’s life was the number of his Zelig-like brushes with history, as cultural figures one after another somehow ended up his chair.

In 1942, while Dr. Wiener was chief dental surgeon at the University of Chicago, Enrico Fermi and his team took over the squash courts under Stagg Field to make the first nuclear reactor. When Mr. Fermi developed vision problems that no specialist could solve, it was finally suggested they look south, at his mouth. Dr. Wiener took X-rays, then extracted an abscessed molar that was pressing on the optic nerve, restoring the great scientist’s eyesight.

Four years later, the novelist Thomas Mann came striding in. The German Nobel laureate, then based in California but passing through town, complained of a toothache on the left side – just like the character Thomas Buddenbrook in the eponymous novel. (In the book, the dentist buy ambien cr 12.5 mg online wrenches out the tooth and soon after, the man falls dead on the street of a stroke – and Buddenbrook Syndrome becomes a medical term for toothache as a potential red flag for cardiac stress.)

Curiously, Mr. Mann appeared to speak no English, instead asking his wife to translate every question, right down to “Where does it hurt?” But at the end of his last appointment, he extended his hand and said, impeccably, “Thank you very much, Dr. Wiener.” And presented him with an autographed copy of The Magic Mountain.

Missing continuing contact with patients, Dr. Wiener left the University of Chicago’s Zoller Clinic and returned to Montreal, where he set up shop on Mackay Street in downtown Montreal. Dr. Wiener’s easy manner provided a kind of sanctuary unusual for a dentist’s office, and he soon built a client list that included Montreal business royalty – among them most of the Bronfman family.

In 1968, Charles Bronfman, then the new majority owner of the fledgling Montreal Expos, arrived for an appointment. It was stressful early days, with stadium issues and other hiccups making league brass nervous and there was a real chance the club would be moved. Dr. Wiener delivered just the right tonic. “My son’s very excited about the team!” he said. The next day, a limousine appeared at the house and when young Neil opened the door, the driver handed him an Expos cap – signed by Mr. Bronfman himself, because no actual players had been drafted yet.

Four years earlier, in 1964, Dr. Wiener took on a patient whose fine dress and old-fashioned manners belied his day job of sausage-making and intimidation. This was Vincenzo (Vic) Cotroni, a.k.a “the Egg,” the local capo for the New York-based Bonanno crime syndicate at the time, charged with overseeing heroin trafficking out of the port. Some called him the Godfather of Montreal. Mr. Cotroni would arrive for his dental appointments flanked by a bodyguard and accompanied by either his wife or mistress. He always paid cash and was the only patient who ever tipped Dr. Wiener’s assistant.

Twin studies have established that, on average, longevity is around 30 per cent determined by genes and 70 per cent, lifestyle and environment. But considering Dr. Wiener’s advanced age, he was undoubtedly very lucky in his DNA. His ferocious good health spoke to a genetic tailwind scientists are still trying to understand. Indeed, nine years ago, Angela Brooks-Wilson, a geneticist and researcher at BC Cancer, collected DNA samples from both Dr. Wiener and his older brother Dave – a near-supercentenarian himself at the time – as part of her study on “super seniors,” investigating the puzzle pieces of healthy longevity.

There is no known case of two supercentenarian men in the same family. The Harvard geneticist George Church put the odds of it happening at north of one in 100 million. The Wiener brothers – Robert, who was 110, and Dave, who was 109 and 324 days when he died – may have come closest. Indeed, an online community called “The 110 Club,” peopled with supercentenarian enthusiasts and curated by the head researcher for the Gerontology Research Group, saluted the pair in a post on Oct. 27, Robert’s birthday. “Together, they are the oldest known brothers of all time – not counting Joan and Pere Riudavets, who were half-siblings. Happy 110th birthday, Dr. Wiener!”

Even well into his 110th year, Dr. Wiener prided himself in not asking for help with routine tasks; he got himself out of chairs and picked up dropped pencils. Apart from hearing issues, he had no real health complaints until the very end.

The only thing he suffered from was heartbreak.

Ella, his wife of almost 73 years, died seven years ago. In her last years, when he was more than 100 years old, he cared for her by himself. Dr. Wiener was not a religious man, but after she died, he burned the Shabbat candles, not so much in honour of her faith, but in honour of her. Although it wasn’t strictly necessary for support, he often picked up her cane while going out. “It’s like holding her hand,” he said.