Every day, in almost every field, someone experiences what can only really be described as a wake-up call. They have gotten things terribly wrong. Somehow, they have ended up on the wrong side. The “second brain” in their gut—that ten-billion-nerve knot—tells them that life can’t go on this way. It just can’t. And so, on moral, or at least deeply personal, grounds, they jump the gap.

The apprehension that you are in some profound sense “living the wrong life” can seem so sudden as to be literally breath-taking—and then so apt as to have been inevitable. When a novelist or short story writer pulls off this effect, what James Joyce called “a revelation of the whatness of a thing” lands hard on readers, and they understand the world in a new way now. When these kinds of epiphanies interrupt the daily routines of real people, their lives can change on the spot. It’s a compelling thing to see. Computer hackers, having served their time and mulled their crimes, go to work for the FBI to hunt hackers. Christian rockers recant their earlier statements of faith. Archconservatives carve out new professional identities as vocal liberals.

If a politician switches parties, we say she has “crossed the floor.” Others in humbler quarters routinely do the same: the ad executive who becomes a media critic, the prosecutor who becomes a social worker, the butcher who becomes a vegan. The shift may be sparked by an external rx meds hub order levitra online event—the collapse of a marriage, the loss of a mentor, a close brush with death—that sharpens the urge to invest what life remains with meaning. But often the reversal is simply the result of a private crisis of conscience. One day, after years of uncomfortable cognitive dissonance, you can’t quite meet your eyes in the mirror. You balk. You confront the choices you have made that have taken you incrementally off course. Then, basically, you defect—blowing up bridges behind you, marching into the arms of grateful new colleagues while the shouts of the furious ex-colleagues ring ever more distantly in your ears.

There’s a branch of mathematics called “catastrophe theory” that deals with turning points in dynamic systems – pregnant moments where a very tiny change in input results in a huge change in output. Catastrophe theory was popular in the 1960s, and it’s been applied outside of engineering, to epidemics and social systems. U-Turn asks the question: might the human mind operate the same way? Are the same forces that make a mountainside give way or a prison population riot at play within each of us? It there a kind of tipping point for the human psyche, a hinge moment where we either snap or transcend? Where we go crazy or ignite with new purpose?

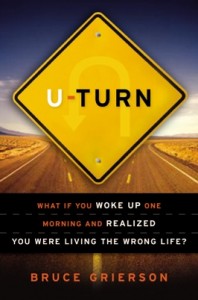

Bloomsbury USA, April

6.13 X 9.25, 320 pp

978-1-58234-584-0