Inside Michael Houghton’s painstaking quest for a cure for Hepatitis C

From New Trail, Spring 2021

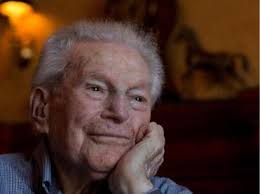

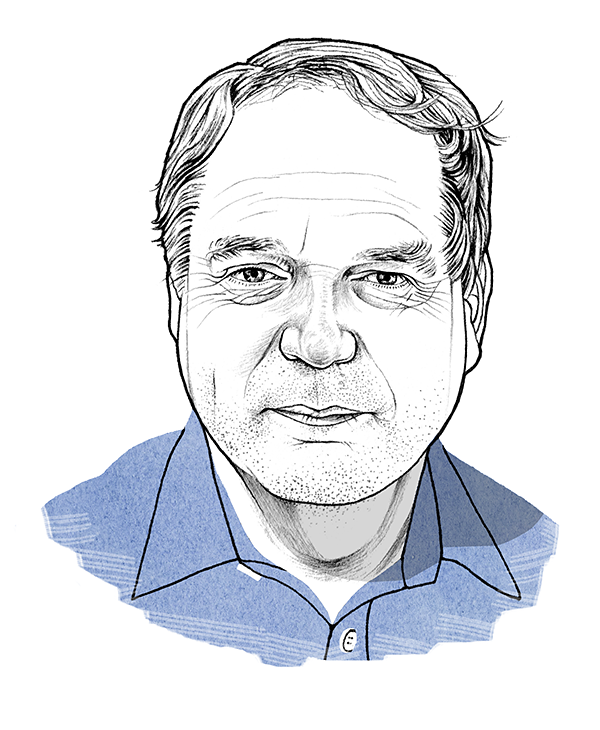

Illustration of Mr. Houghton by Adam Cruft

When Chiron Corp., a small biotech company in California, hired a young scientist named Michael Houghton in 1982, it was already clear he was an exceptional scientist.

Several top biotech companies had offered him senior scientist positions based on research he’d done since obtaining his PhD in 1977 from King’s College London, in England. When Chiron called, Houghton was researching human interferon genes at a U.K. research institute of the large U.S. pharmaceutical company, G.D. Searle & Co.

Soon after Houghton arrived at Chiron, he learned about a mystery unfolding in every country.

A dangerous new pathogen that attacked the liver was running amok in the global blood supply. Left untreated, it could cause cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and cancer. It wasn’t hepatitis A and it wasn’t hepatitis B. Whatever it was, it was brutal. Apart from turning a blood transfusion into a game of Russian roulette, it plagued the world’s most vulnerable and stigmatized people when they shared a needle — for it seemed to spread through contaminated blood. Roughly 150 million people worldwide were infected with it.

Houghton decided to switch fields and devote his lab at Chiron to finding the mystery virus.

“I thought, ‘Yeah, this will be a good purpose for my lab,’ ” Houghton recalls.

He had no idea what he was in for.

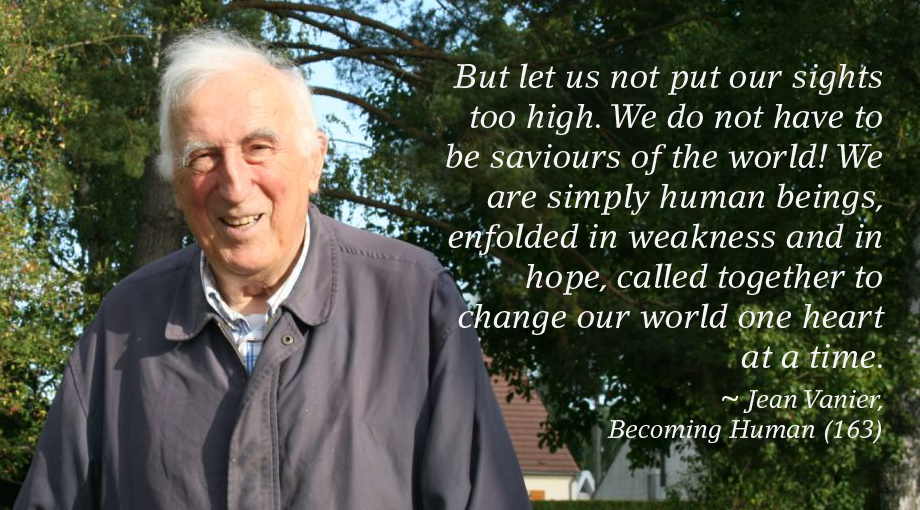

By now you probably know the man we’re talking about. In October, he won the Nobel Prize in medicine, sharing the honour with Americans Harvey Alter and Charles Rice. Houghton, a virologist in the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry and director of the Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute at the University of Alberta, is the first scientist based at a Canadian university to win a Nobel in medicine since Frederick Banting discovered insulin at the University of Toronto in 1923.

And that, you might assume, is the story in a nutshell: young researcher gets on the train and hops off 40 years later at the summit of human accomplishment, feted by the world as a hero.

But of course, the story isn’t that tidy. And the final chapter is still being written.

“You want to know what it takes to win a Nobel Prize? You do something that many people think is not possible,” says Lorne Tyrrell, virologist and founding director of the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology, which encompasses the Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute that Houghton leads. Both work in the Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry.

Indeed, it’s necessary to not realize it’s impossible in order to be able to do it, as the Nobel-winning physicist J. Michael Kosterlitz once framed the task.

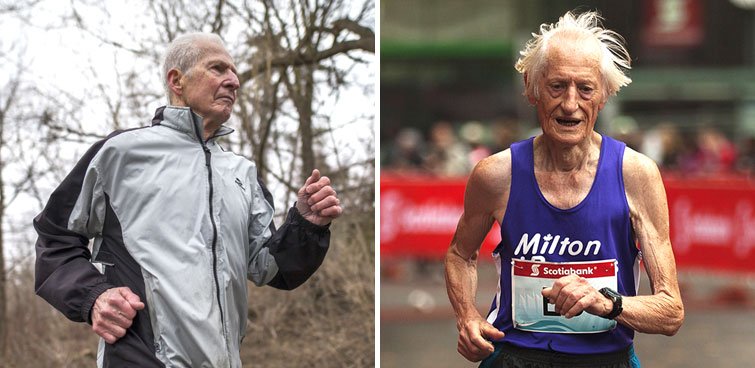

In video meetings with media following the Oct. 5 Nobel announcement, Houghton presented to the world an expression that was … complicated. A mixture of joy, relief and gratitude, for sure. But the face of the scientist, now 70, also hinted at the kind of determination you’d expect of someone who deals in the impossible.

In 1982, the disease Houghton decided to tackle was known only as NANBH — non-A, non-B hepatitis, as in not caused by hep A or B viruses. A mysterious blood-borne disease defined by what it wasn’t. This would become his quest: to chase a shadow.

Together with Qui-Lim Choo, whom he recruited in 1983 along with Amy Weiner, Kang-Sheng Wang and Maureen Powers, Houghton set to work. One of the things that had slowed progress on NANBH — let’s call it HCV, the hepatitis C virus, since we know now that’s what they were seeking — was the lack of suitable animal models. Other than humans, hep C is only known to infect chimpanzees.

Houghton visited the lab of Daniel Bradley of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an expert in the NANBH chimpanzee model. With Bradley’s collaboration, the Chiron team extracted nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) from infected chimps and patients and cloned them to create vast libraries containing millions of nucleic acid sequences. They began sifting through them for one that looked as if it didn’t belong — a task akin to finding a single typo in a dictionary.

These days, with modern techniques that vastly speed up the copying and sequencing of segments of the genome, virology is a different beast than it was then. Nothing in Houghton’s tool kit at the time was quite up to the scope of this endeavour. “The methods we were applying were not sensitive enough,” he says. If today’s technology had been available back then, Houghton says, “it probably would have taken seven weeks” to find the mystery virus and sequence it.

Instead, it took seven years.

It didn’t help that no one really knew what kind of pathogen they were looking for. Was the virus like hep B or yellow fever — or even a prion? Or maybe it was a retrovirus like HIV. Houghton’s strategy was to go wide, trying many different molecular approaches at once based on the scientists’ best guesses. It was like fishing with multiple rods over the side, each hook carrying different molecular bait. At one point, more than 20 different approaches were in play.

Their work was painstaking. And fruitless.

“After two or three years,” Houghton says, “we were still shooting blanks.”

The path to any Nobel Prize is paved with failed experiments, almost by definition. The breakthroughs that win a Nobel tend to be innovations wrought by failures that force you to rethink and try new approaches.

One day in 1985, three years into the research, Houghton went next door to the lab of George Kuo to discuss a new approach Houghton had been considering involving the generation of monoclonal antibodies against HCV. That key discussion convinced Houghton to try an immunoscreening approach to bacterial clone libraries. At about the same time, Bradley suggested the same idea.

So, the Chiron team put another fishing rod over the side, so to speak.

The tactic, never before tried to identify a new virus, would use antibodies — proteins in the blood that bind to foreign substances — to help detect the virus. The team would copy the DNA and RNA from chronic hep C carriers into DNA in bacteria and make libraries of many millions of bacterial colonies. Then they could screen the libraries using samples from patients with chronic hep C.

If the idea worked, the antibodies would sniff out and bind to the foreign stowaway, the hep C virus, in a rare one-in-a-million colony.

Over the next couple of years, Houghton and Choo sifted through the cloned DNA and RNA in 11 different bacterial libraries — millions upon millions of genetic sequences. They found nothing at all that might be the elusive quarry.

Nothing.

It has been said that people, like teeth, come in two types: incisors and grinders. And surely this applies to scientists, too. Incisors make an early impact with a provocative paper, enjoy early fame and then often fade from view.

Houghton is unquestionably a grinder. People who’ve worked with him say he is like a dog on a bone. “What distinguishes Mike compared to other researchers is that he zeroes in on a goal and goes after it, and he just never lets go,” says John Law, lead virologist in the Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute and a research associate in the Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology. “He’s not going to fall back on Plan B just because Plan A is hard.”

Back in 1987, after five years of trying and failing to find hep C at Chiron, Houghton was beginning to feel some pressure as the project leader responsible for the research. “The investors put pressure on management, and management put pressure on me.” Houghton knew he was close to being cut loose.

He didn’t particularly care. This was his mission: to fight the toll of disease on so many lives around the world.

“You can go ahead and fire me,” he remembers telling his boss. “I’ll just continue to work on this elsewhere.’ ”

The needle in a haystack

By the fall of 1987, Houghton and his team at Chiron had tried 30 to 40 different approaches and sifted through literally hundreds of millions of recombinant clones.

Up to that point, Houghton and Choo had been screening the bacterial libraries with serum derived from the rare patients and chimps that had recovered from NANBH infection, assuming they would have the highest antibody levels. They decided instead to use serum from NANBH patients who had not recovered.

One day, while combing through a bacterial library — in a sample that contained a bit of contaminating “goo” that made it look so unpromising it was almost thrown out — Choo found something. It was “a very tiny little clone,” Houghton says. The wee-est fragment of a copy of … what? He and Choo scrutinized it over several months. It looked different from anything they’d seen, not derived from human or chimp genomes. Foreign.

It was a single, small nucleic acid clone derived from a large molecule typical of RNA viruses. Houghton and Choo also showed that the RNA encoded a protein to which most NANBH patients had antibodies that were not present in uninfected control patients. Based on this, Kuo developed a method to test a large number of patients, which confirmed the presence of antibodies in NANBH patients and not in control patients. As Houghton and Choo found more and more related clones and determined their sequence, they saw very faint but significant similarities with known flaviviruses such as dengue and yellow fever. That was when they knew they had it.

Houghton disclosed the finding at a seminar at the University of California, San Francisco, in 1988. Some hepatitis experts were skeptical, even after seeing the data. But not Houghton, Choo and Kuo. “We knew we had it,” Houghton says. “I don’t take drugs to feel good, but I was on a high for two years afterwards.”

Two years. That’s how long it would take to use their precious little snippet to sequence the whole virus. And then to convince the world, with at least eight rounds of verification, that they had the real deal.

Deadly viruses can be quite beautiful. Hepatitis C turned out to be caused by an RNA virus very distantly related to tropical diseases like yellow fever or dengue. Under the microscope, it was small and round and enveloped with surface proteins — a bit like the now-familiar SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 — the better to get its hooks into its host.

With a blueprint to work from, the team rushed to develop a test to screen blood for the newly identified contaminant. The team announced its blockbuster discoveries in Science in 1989: the isolation of the hepatitis C virus and a test that could successfully detect the virus in human blood.

Blood banks around the world finally had the gatekeeper they needed. Until then, the odds of getting hep C from transfused blood had been around the same as drawing a face card in a deck. With new screening tests that could detect tainted blood in advance, HCV was virtually eliminated from the Canadian blood supply by 1992.

Beyond making the blood supply safer, Houghton et al. published the genetic sequence for HCV, which allowed researchers to develop antiviral drugs to treat hep C. It looked as if the hard work was over.

It wasn’t.

The promise of making lives better

This is a story about hepatitis C. But it’s also a story about hep B — for it was Lorne Tyrrell’s work on hep B that, in a roundabout way, built the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology at the U of A. From Tyrrell’s research, pharmaceutical company Glaxo produced the antiviral drug lamivudine, the first oral treatment of chronic hepatitis B, and sank enough funds into the U of A to begin robust virology research and development. Hong Kong billionaire philanthropist Li Ka-shing decided to invest in the scientist whose work had improved, if not outright saved, millions of lives: one Lorne Tyrrell. It was the infusion of $25 million from the Li Ka Shing (Canada) Foundation that attracted $52.5 million from the Government of Alberta through Alberta Innovates. The funding allowed Tyrrell to vastly expand his budding virology institute and to found the Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute in 2013.

The new institute was tasked with transforming virology research into treatments, drugs and vaccines that would directly improve people’s lives. And Tyrrell had just the person in mind to lead it.

It began with a phone call in 2009. It was a call that was bound to happen sometime. Tyrrell, in his lab, had made his mark with hepatitis B. Houghton, in his lab, had identified the hep C and hep D viral genomes during his time at Chiron. Between them, they nearly covered the alphabet. It was about time they stopped circling each other like double-helix strands and met.

Houghton was driving through San Francisco one sunny lunchtime when he got a call from Tyrrell. Houghton was then at a different small biotech outfit, where he was working on herpes viruses. Tyrrell floated the news that a new institute within the Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology would focus on translating lab discoveries into practical and commercial applications. It needed someone to run it. Tyrrell wanted an outstanding virologist to apply for a grant from the new federal Canada Excellence Research Chair program, which would guarantee funding for seven years.

“Do you know anyone who might be interested?” he asked Houghton.

It was a nervy overture. If there is such a thing as a rock star in the world of virology, Houghton was it. He had won the prestigious Albert Lasker award in 2000. In 2003, his team had developed a SARS vaccine to address the major health threat of that year. (The SARS virus disappeared quite quickly, but had the vaccine been commercially manufactured and stockpiled, Houghton believes it could have changed the course of another SARS virus outbreak: COVID-19.)

On the phone with Tyrrell, Houghton fished for a couple of names of folks who might be interested. “But you know,” he said finally, “I might be.”

It was exactly what Tyrrell had wanted to hear.

Research that cures disease and improves people’s lives — this is what drives Houghton and turned his eyes toward Edmonton.

Canada typically lags behind the United States in this type of “bench to bedside” research, and Houghton was thrilled to see the U of A cranking up that commercial energy. It was one of the things that made him take the job.

After arriving on campus, he wasted no time in hiring a vaccine team that included a dozen scientists and technicians, many of them Canadian, with Tyrrell as a close collaborator. The goal was to work across disciplines to turn basic research into a safe human vaccine to prevent hep C.

Spirits were high. But the vaccine team would soon run into major challenges — owing partly to the sneaky nature of the hep C virus.

“The virus is difficult in a few senses,” says Law, the lead virologist on the vaccine team. Each strain has a wildly different genetic signature. “It’s almost like a person who keeps dressing up differently to get into a bar he was kicked out of,” says Law. “He keeps putting on different clothes to get past the bouncer multiple times.”

Vaccines trick the body’s immune system into building a defence against a phantom scourge it thinks it’s encountering. The hep C vaccine being developed at the U of A is made from a cultured human cell tracing back to a single donor. It isn’t a weakened copy of the whole virus but rather a little piece of the outer protein shell. And that shell is super-delicate. Like a soufflé.

“It comes apart easily,” says Law. “Also, the cells don’t like to make this protein. Other vaccines, it’s almost like making a piece of copper. It’s easy. But now we’re making a piece of gold. And we need to give it to everybody. So, we need to have an efficient way to go to the gold mine and extract enough to give it to everybody. And keep the costs down.”

Despite the challenges, something happened in 2013 that lifted everyone’s spirits.

Law and his team were experimenting with a new technique. Many were skeptical it would work, but after many trials, they got a promising result. The technique seemed to neutralize or prevent infection for multiple different strains of the virus. They had solved, as Law explained it, the “getting-past-the-bouncer” problem.

“I remember the day we sent [Houghton] the data,” Law says. “It was right at the time he had to give a report to the funding agency.” At a media conference, Houghton coolly presented the news. The U of A had made, for the first time, a hep C vaccine that appeared to work against most known strains of the virus.

It was a game-changing development — a development that led to a promising hep C vaccine that Houghton’s team hopes to take to human trials this year or next.

“We’ve got a lot of partners lined up around the world — the United States, Germany, Italy and maybe Australia — to test it in the clinic as soon as we’ve made it. And I think it has a good chance of working,” says Houghton.

The ultimate goal: eradication

Houghton is sometimes asked why we need a hepatitis C vaccine at all. After all, thanks to his original hep C discovery, drugs now exist that can quickly cure most patients with few side-effects. His best argument goes like this: Any treatment, no matter how effective, is still just playing whack-a-mole with the disease. Despite advances in treatment, hepatitis C has infected an estimated 170 million people worldwide, while 71 million live with chronic infection that can lead to liver disease and cancer. Ultimately, a vaccine is the only way to eradicate it from the planet.

And quite apart from the cost in human suffering, there’s the financial hit. Tyrrell likes to say that if you accidentally drop your hep C pill down the sink, you’d better have the nearest plumber on speed dial. A full course of treatment costs around $60,000. An effective HCV vaccine would save Canada’s health-care budget close to $1 billion in antiviral drug costs over 10 years, Houghton estimates. “If you figure out how much it’s going to cost to treat those people with drugs, versus how much to vaccinate, then it’s night and day. It’s at least an order of magnitude cheaper to vaccinate.”

Every year since 2012, Tyrrell had been nominating Houghton for the Nobel Prize. And every year Tyrrell had called the university’s president and dean of the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry to say they should keep an ear out.

He knew in his bones that Houghton was deserving. “To win a Nobel Prize, you’re making a discovery that is transformative,” he says. The hep C discovery has saved or transformed millions of lives, if you count the curative drugs developed from it and the blood screening that prevents the disease in the first place. An annual international conference around hepatitis C has been running for 27 years — a whole discipline that wouldn’t exist without the work of Houghton’s team.

Then last Oct. 5, at two minutes to 4 a.m., Tyrrell woke up as he does every year to check his phone for Nobel news. Nothing. He waited a few minutes. Nothing. And then … the kind of news that chalks a high‑water mark onto a whole life.

Houghton was in California. His phone rang at 3:10 a.m. local time. The Nobel committee didn’t have his phone number, so it was his friend, Tyrrell, who woke him up.

“Congratulations, Mike,” he said. “You just won the Nobel Prize.”

There was silence. Ice ages came and went. It was one of the greatest moments in the history of the University of Alberta.

Except.

What if Houghton — the man Tyrrell had hired partly for the kind of stubborn decisiveness that made him an awesome research scientist and a refuser of prizes on principle — refused the Nobel?

After all, he had refused the Gairdner in 2013, Canada’s most prestigious award in science, when he learned that it would go to him alone. To his mind, his former colleagues were an inseparable part of the hep C discovery. Choo was his wingman, working 100-hour weeks at the bench for years on end. And Kuo, well, he was the one who had convinced Houghton to try the approach that ultimately worked.

His frustration was not just about recognition. It was, and continues to be, that the world seems not to acknowledge the way science works, he says. Scientific discovery is not some kind of transoceanic row by a solo sailor. There is no single “aha” moment by the genius in charge. Innumerable small wins along the way advance the technology in ways the world never sees.

“I don’t think I’m being unduly ethical,” he says now. “I’m just being honest. When you’ve worked with people for a long time and you know that they’ve made key contributions, it’s just basic honesty.”

Which is why Houghton, after agonizing, told Tyrrell in 2013 he wouldn’t accept the Gairdner (or the $100,000 that goes with it), a gesture that was unprecedented in the award’s 54-year history.

Anticipating the same dilemma this time, Tyrrell had video-called Houghton the previous Friday for a temperature check. Just as he feared, his colleague was deeply conflicted. “Michael, we can’t go through this again,” Tyrrell said. “Please. Look straight at me and tell me, ‘I will accept the Nobel Prize if it’s awarded to me.’ ”

Houghton said he would.

It’s customary for Nobel acceptance speeches to be a little bit lighthearted. When Richard Taylor won the 1990 Nobel in physics for his work at Stanford, he said: “We were asked to be witty. But after a great deal of reflection I have decided that quarks are just not funny. … Perhaps next year the Royal Academy will award the physics prize to someone in condensed matter physics or general relativity. Those are hilarious subjects.”

Houghton’s speech wasn’t like that. Instead, via Zoom from his home in San Francisco, he laid a sober bread-crumb trail of his path to the hep C discovery, recognizing by name everyone who contributed along the way. Receiving a special hat tip were Choo, Kuo and Bradley.

It was Houghton’s way of cutting the Gordian knot. He was upset at how major science awards tend to prop one scientist up in the shop window. But he was honoured.

“It would be too presumptuous to turn down a Nobel,” he says. He owed it to the U of A, to Tyrrell and to his colleagues not to refuse it. “And also, by accepting the Nobel,” he says, “I’ve been able to get the message out loud and clear: ‘This was a team effort.’ ”

After the announcement, the journal Nature reached out to Kuo and Choo for comment. Both took the high road. Kuo admitted he was disappointed to have been left out but was pleased to have had a hand in the accomplishment. And to have been able to model for his children “how important it is to work hard on something that you feel passionately about.” Choo broke down and cried — not with bitterness but with joy. “It’s my baby; I’m so very proud,” he told Nature. “How can I not be proud?”

The magnanimity breaks your heart. But by Houghton’s lights, gracefulness in the face of discourtesy should never have been asked of these two men.

“As knowledge and technology grow exponentially around the world and with an increasing need for multidisciplinary collaborations to address complex questions and problems, there is a case to be made for award committees adjusting to this changing paradigm,” he wrote in an op-ed in Nature in 2013 after refusing the Gairdner.

“What matters is that you are successful with a group of people. I firmly believe the ethical way forward is for all institutions to be more inclusive,” he adds today.

That is science’s bottom line. You’re always building on previous work. No one is freestyling. It takes a team to win a Nobel Prize.

A quirky fact on the way out the door here: Winning the Nobel Prize buys you almost two more years of life. The number comes from a 2007 study based on the lives of 528 Nobel recipients and nominees from 1901 to 1950. No one has been able to explain the phenomenon, though some have speculated that the spike in status may somehow boost the immune system. Perhaps the body knows it has earned a victory lap.

Or maybe the type of person who wins a Nobel is too dedicated to give up those two extra years in the lab.

The famed Merck virologist Maurice Hilleman, who developed eight of the 14 vaccinations that kids get today, carried in his pocket a list of childhood viral diseases that had yet to be conquered. This was his to-do list. When he knocked one off (rubella: check) he would literally cross it off and move on to the next.

Houghton has something of that same mindset. Shouldn’t it just be a normal thing to want to fix the world? And to believe that you can?

“If you really think about it, it’s almost a disgrace that we know so little about so many major diseases,” he says. “Alzheimer’s, Lou Gehrig’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis. We are capable of curing those diseases. Why haven’t we? Because there’s not enough funding? Yes. But also, there’s not enough cultural momentum to focus on disease. And that sounds ridiculous, doesn’t it?”

Houghton has his own to-do list, and it is Hilleman-like. The applied virology institute is collaborating with a wide international network to research, among other things, a Group A streptococcus vaccine, novel therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease and cancer immunotherapy.

“I’ve always felt that contributing to disease solutions is well worth all the failures, all the frustration, all the funding issues, and all the politics,” Houghton says.

“Millions of people are dying and suffering from so many diseases around the world. Working for 40 years on HCV, and several years on other diseases, is the least that I can do.”

*