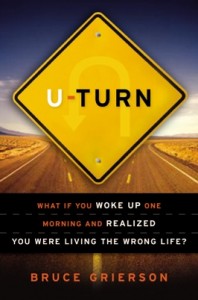

From the archives: East Meets West in the Dentist’s Chair

From SATURDAY NIGHT magazine, 2002

For whatever reason—and there’s endless scope to speculate – pain is a hot topic these days. “That’s gotta hurt!” we say of the extreme snowboarder who lands face-first while jumping a Volkswagon, or of our friend’s kid who flashes her tongue stud or lumbar tattoo. But we’re fascinated. In an age where pain is optional, it has acquired a strange new cachet.

On today’s maternity wards, experiments in mystical stoicism have replaced old-style epidural-aided childbirth (which at least offered mothers-to-be some relief) with “natural childbirth, where lucky women get to sweat and holler and squeeze the doula’s hand, the pain simply the price of being fully present in the moment. The Dene and the Inuit of the Northwest Territories would understand. Many of their traditional games – the mouth pull, the knuckle hop – involve the mutual affliction of pain. “If we know how much pain we can take,” an elder named Big Bob Aikens explained to writer John Vaillant not long ago, “we know we can survive if we are injured.” Most of us below the tundra line are so far away from needing pain for that reason that it’s hard to fully appreciate what Big Bob is getting at. But the possibility glimmers on the periphery of awareness that maybe the Inuit are onto something. Maybe anesthetizing pain is a bad idea, evolutionarily. Maybe learning to feel pain, to take it, to “live inside” it, to study it, to re-engineer our relationship with it, is part of the secret of advancing the species.

There is, of course, another, more immediately relevant reason to study pain: as pain treatment goes, so goes the future of medicine. How we decide to deal with pain matters, now possibly more than ever, because pain disproportionately affects an enormous and growing number in an aging population.

And it’s hear that a clear division has emerged on which direction we ought to pursue. Ask a Western doctor what the future of pain relief is, and he or she will probably start naming drugs that end in x. Western medicine has cast its lot with pharmacology, and, increasingly, biotechnology.

But at the same time, and in record numbers, the afflicted are looking for something different. Collectively, we seem to be letting our guard down about those crazy Eastern remedies that at least do no harm, and may do some good. (British Columbia, where I live, was the first province where traditional Chinese medicine was recognized as a regulated discipline.) Herbs, guided fantasy, acupuncture, magnets, hypnosis, virtual reality, prayer: people will reach for anything when they’re in pain and the old standbys haven’t done the job. The “proof” that any of these “natural” remedies is effective – that is, double-blind controlled-study proof, Western science’s standard – is scanty at best, but the nature of the target, pain, is ephemeral enough that the phrase “controlled study” can seem hopelessly paradoxical.

What is clear is that the mind, when it comes to pain, is more powerful than we ever imagined. Pain, like, time, is an illusion. We interpret it as discomfort because discomfort is nature’s way of ensuring a damaged area gets attention. But is there anything to say that we can’t learn to “read” pain signals dispassionately, as just so many lines of source code, and remove the discomfort from the equation? Or even learn to interpret pain signals as pleasurable – so-called “eudemonic” pain? Hindu mystics have done it for centuries. As that stoic philosopher Arnold Schwarzenegger put it in The Terminator, “Pain can be controlled – you just disconnect it.”

Was Arnie right? I have decided to find out.

It happens that I am one of those people who never had their wisdom teeth removed. Now all four of mine sit like tiny thrones sunk in soft tissue – inviting a controlled test. I will have the teeth on the right pulled the Western way (which is to say, by an oral surgeon and with ample drugs before and after) and the teeth on the left pulled the Eastern way (by a holistic-oriented dentist using a cocktail of New Age measures, no anesthetic.) My own theory is that since the more soulful, creative right brain controls the left side of the body, I ought to be able to recruit some natural pain relief from there. Or at least draw on reserves of faith.

I will turn over my body – my mouth, at any rate – to science. East vs. West: may the best side win.

WEST

Dr. Martin (Marty) Braverman is one of the top oral surgeons in B.C. His office is in a mall.

Braverman can extract a couple of teeth in the time it takes to get your oil changed. On a busy day he might pull a hundred teeth. You pay a little extra for a guy like Marty Braverman, because he is a specialist and because he boasts a very low dry-socket ratio. (A dry socket, in which the bone holding the tooth becomes exposed to air, is the very definition of pain.) “Will I be able to drive afterward?” I’d asked the receptionist.

“Can you drive now?” she said.

“Yes.”

“Then, yes.” Ba-rum-bum.

Sitting in Braverman’s chair, I survey a rolling cart with a few silver instruments on it. The smell of a dentist’s office provokes a kind of primal fear, and, fast on its heels, the urge to bolt. I have to remind myself: This is the easy side.

Braverman is short and bespectacled and almost alarmingly casual in manner. He’s wearing khakis. With a needle as fat as a fountain pen, he injects, lidocaine, but as he has applied topical anesthetic to numb the gum first, I don’t feel the needle go in. I don’t feel a thing.

“Now, lidocaine usually has about a three-hour duration,” Braverman says, “so in three or four hours you’re going to experience some discomfort.” A nurse pokes her head in to remind Braverman that he has a lunch date in twenty minutes.

He goes to work on the lower right-hand tooth, the trickier one because it’s half-buried. He makes an incision. “What we’re going to do is push the gum back away from the tooth,” he says. “You’ll feel some pressure as we do that.” A scratching sound, a cat at the door. He removes a bit of bone to create some space to lever the tooth up and out. The drill roars. Through the window, I can see the traffic light, hung on a wire over the intersection, being blown so far off plumb by the wind that the motorists can’t tell what colour the light is.

Braverman has the tooth out in two minutes, 35 seconds. He asks for a needle-driver, so that he can “re-approximate” the gum with some stitches. He packs the hole with a dissolving sponge and packs my cheek with dexamethasone, an anti-swelling drug.

The top tooth ought to go even faster, and it does. Braverman levers an instrument called an elevator – essentially a primitive wedge – between the tooth and the bone, grabs onto the tooth with the forceps, and, boom: done. One minute, 25 seconds. I have barely warmed up the chair for the next person. Pain? There has been none. The procedure is over so quickly as to be disorienting. This feels like cheating, the way plane travel feels like cheating, bridging distance you somehow haven’t earned.

Braverman prescribes Tylenol 3 and the antibiotic amoxicillin – a prescription I fill one floor down in the mall, before driving home. The cost is $250. There’s an industry joke about a guy who receives the bill from his oral surgeon. He’s outraged. “Three hundred dollars for 15 minutes’ work?!” The surgeon replies, “Would you rather I’d taken an hour?”

A problem arises as I try to monitor the degree of pain I experience during recovery: how do I measure it? Most doctors acknowledge that the task of calibrating pain is almost impossible, since the amount of pain people feel is ultimately subjective, varies wildly from patient to patient, and is influenced by factors such as mood and expectation. All of the pain scales thus far devised are imprecise, and in fact no one has improved on the old “On a scale of one to 10, how much does this hurt?” The pain I feel on Day 1, after the extraction, is about a 2.

On day 2, the pain climbs to three, and requires a couple of T3’s to keep it in check. I try to pay attention to the pain. It diminishes, narrowing to a little, lingering ache just below the right temple, then migrates to the hinge of my jaw. By Day 4, it is largely gone. For all intents, the right side, the Western side, is over – hardly more psychically disruptive, overall, than a bad haircut. The persistence of a very low-grade headache makes me wonder if there isn’t, just possibly, a little infection, so I start taking the antibiotics again, three a day. A week later I take a closer look at the label on the bottle: “Three a day until finished, as directed by Dr. Salzman.” Dr. Salzman? Oh yeah: the guy I sometimes see from the travel clinic down the street. I have been taking pills for altitude sickness.

EAST (The Preparation)

Canadians spent about $4 billion on alternative therapies last year, and more than two in five say they use some kind of “complementary” medicine. In most cities you can now find a holistic dentist who will manage pain with hypnoanaesthesia or herbology or acupuncture instead of burying it with sedatives or anesthetic. It would be an exaggeration, though, to say that the masses are flocking to these folks.

“People don’t like to feel pain,” says Dr. Craig Kirker, the founder of Biological Dental Investigations, a consultant at the Integrative Medicine Institute of Canada in Calgary – and the practitioner who has agreed to take me as a test subject. Kirker often uses acupuncture in his treatment of patients, usually ones who are terrified of the kind of big dental needles that deliver lidocaine (and for whom, therefore, the reduced pain felt with acupuncture is preferable to the full-throttle pain of no treatment at all). “When you’re frozen with anesthetic, you’ll feel, on a scale of one to 10, zero, maybe point-five. If you have no freezing you might feel a nine when it gets close to the nerve. With the acupuncture you feel about a four. And it’ll peak to about a six. Just once in a while. You know, just kind of like: ‘zing.’”

Regarding my own personal experiment, Kirker is curious, even keen, but offers no guarantees. No painkillers before, during or after? “If you’re just popping a tooth out, it’s not such a big deal,” he says. “If they have to touch the bone, you’re probably going to want freezing. It’s a little different kind of pain down there. But it’d be interesting.”

Kirker sets up the extraction for three weeks hence. He recommends a couple of ways I can prepare. One is a visualization exercise popularized by Jose Silva in a classic of New Age literature called You the Healer. Basically, the subject relaxes by counting backwards from 50. You imagine your hand immersed in a bucket of ice water. You leave your hand in the water for 10 minutes. Then you withdraw it, stiff and numb, and apply it to your face, where the numbness transfers to the jaw and settles deeply into the bone.

“Here’s another little tidbit,” Kirker advises by e-mail. “Get into your quiet space and have a little conversation with your wisdom teeth and jaw. It would be nice if they felt OK about parting ways as well. I know it sounds a little flighty, but I have actually run into cases where this could have prevented a lot of trouble if we had listened more carefully.”

And so Jose Silva joins my night-table stack, atop Mark Salzman’s novel Lying Awake. In that book, a nun named Sister John has been suffering from killer migraines, which we later discover are linked to epilepsy. “I try to see pain as an opportunity, not an affliction,” she explains to a neurologist. “If I surrender to it in the right way, I have a feeling of transcending my body completely. It’s a wonderful experience, but it’s spiritual, not physical.”

EAST (The Indoctrination)

The IMI, a cozy little brick building not far from downtown Calgary, is on the frontier of the field of “integrated medicine.” Its mandate is similar to Andrew Weil’s bailiwick at the University of Arizona – to get the two solitudes, Western and Eastern medicine, to meet for lunch. Mind-body medicine is about breaking the old dichotomy – not “East” or “West” but “the medicine that works at the right time for the right reason.” “The body is capable of healing itself,” the Canadian alternative-medicine pioneer Wah Jun Tze often said. IN fact, perfect health is the body’s natural state, and anything that interposes itself in that process, the mind-body tribe says, is probably hurting more than it’s helping in the long run.

I arrive the day before the scheduled extraction. My vow to do this side the Eastern way forces the direction of treatment somewhat. Kirker will work as part of a team: he’ll do the prep work and the acupuncture while a colleague named Bill Cryderman, a dentist who is on the same page with IMI philosophically, will pull the teeth. “We could have gone with an oral surgeon, but I thought you’d have a more exciting experience with Bill,” Kirker says. But before I meet Cryderman, there’s a little “tuning up” to be done.

“Here in the West we’re hunt up on the double-blind placebo study,” Kirker says as I frump into the chair next to a “bioresonance” machine called a MORA. “First we observe. We make theories. Then we test those theories, and that’s science. When Newton proposed an invisible force called gravity, they almost threw him out of the institute – but then they started testing and found out he was right.”

Craig Kirker is a nice guy. If Mr. Rogers ever decided to have a dentist on his show, Kirker would be the man he’s invite. He has a habit of telling an anecdote with a surprise ending involving spontaneous or dramatic healing, and punctuating it with “Interesting.” The MORA machine is making high-pitched squeals. Its job, Kirker says, is to detect imbalances in my body’s “harmonics” and try to kick me back into plumb. A nurse jots down the readings she’s getting. Apparently I’m a little out of balance,” “possible from the plane ride,” Kirker offers, charitably.

Next, in another room, my autonomic reflexes are tested to determine how much my body reacts to anesthetics the dentist might have if the pain proves too much to bear. Kirker puts a number of different samples in a little receptacle, one by one, and determines how they conduct energy through an acupressure point in my finger.

In still another room, I lie on a massage table with an oxygen mask over my mouth. I get a fix of ionized oxygen for 16 minutes – eight minutes of positively charged ions followed by eight minutes of negatively charged ions – which Kirker tells me has a general “detoxifying” effect and boosts my immune system. (If you could take a picture of the energy field around my body, he says, you’d see that after the oxygen had saturated the cells, the energy field would have expanded to Michelin Man dimensions.)

Then we add light. From the hood of a “biophoton machine” poised over my scalp, tiny red pulsing diodes send light energy into my body, filling me, Kirker says, with qi energy. A magnetic ring around my ankles catches energy that would apparently otherwise be lost, and sends it back into my body.

Finally Kirker puts a tiny vial of liquid in the “honeycomb” – a device that takes the frequency signature of whatever you put in it and feeds it through the lights. The liquid is a homeopathic remedy created from a flower essence – an ultradilute solution of dew collected from a flower petal in a meadow in Western Canada just as the light of dawn struck it – selected for me by an IMI staff “intuitive” named Iris.

“We’re working on you from all levels,” Kirker says.

Now, there is plenty in New Age medicine to be suspicious of. In my suitcase is a thick folder full of articles that take the air out of exactly the sort of thing we’ve been doing. But I haven’t read them yet. I’m highly motivated to believe. What’s going on here seems nutty, but my job is to take my own cynicism out of the equation at least until my teeth are handed to me in a sack. No theories, no baggage, just direct experience.

As he finishes the tune-up, Kirker tells the story of his own drift from hard science to the speculative fringe. How, almost as a lark, he played along with the leader of a workshop called “Body Symptoms as a Spiritual Process,” and allowed the possibility that symptoms happen for a reason and that the painful kink in his neck was just his body’s subconscious trying to tell him something. (The kink vanished.) And how, a while later, a naturopath using a similar technique managed to cure him of chronic abdominal pain. As far as extra-normal talent goes, for that matter, Kirker’s associate Iris, the “medical intuitive,” has a reputation for being downright psychic. Sometimes she turns up in pictures of gatherings she wasn’t even at. And here she is now, poking her head into the treatment room. “Will you be there tomorrow?” I ask.

“Not in body,” she says.

“Then how will I know if you’re around?”

“I’m a little clumsy,” Iris says. “If somebody knocks something over, that’s me.”

EAST (The Extraction)

Bill Cryderman’s workplace feels less like a dentist’s office than like the “pioneers” wing of a museum of natural history. Water rills down a slate waterfall and trickles lazily into a catch basin. Fire blazes in a hearth. A pair of snowshoes sits propped in a wall niche. And overhead, positioned so that its ribs fill the field of vision of the prone patient, is a ‘40s-era wide-bodied wooden canoe.

Cryderman himself is a small man with a sort of jocular confidence. “Good to meet you,” he said, emerging from behind a partition and pumping my hand. “Are you all psyched?”

I am lying in his high-tech dental chair. With a low hum, parts of it move to adjust to my contours. Some money falls out of my pocket onto the floor. “That’s the automatic coin-remover,” Cryderman buy ambien online visa says.

He draws himself in close, trying to gauge my level of trepidation. “You know we have a backup, right?” He means lidocaine. “It’s just for your mental security. I don’t want to give you a back door. This is going to work.”

It’s hard to tell whether Cryderman’s as certain as he seems to be, or as certain as he needs to be fore me to believe him.

There comes a point – and actors and speakers must feel this – when apprehension becomes a bigger burden than the thing you’re apprehensive about, and you actually wish yourself forward in time to meet the event. I felt that way this morning. But now I’m in full retreat, my stomach in coils.

For the past week, I’ve been practicing the ice-bucket exercise. In theory, I should be able to effect an actual physiological change. In other words, I’m not just fooling myself into thinking the area’s growing numb – it IS growing numb. Neurons generate electrochemical charges that actually block the pain messages coming back from the brain. In theory.

Craig Kirker is beside me. He seems quietly stoked. He is the pit crew, the doula, overseeing the acupuncture. Carefully, he hooks up tiny needles to acupressure points in my right ear, left hand, left food and face. Some of these needles are basically just electrodes, through which a mild current (called, oddly, a tsunami) will run from a machine called, unpromisingly, an Accu-O-Matic. There’s very little sensation: the needles hardly feel as if they’ve penetrated the skin. This could easily be a total ruse. “Now I’m just going to dial it up,” Kirker says. “The frequency you’re on right now is for healing.”

What am I doing here? No, really, literally, what am I doing here? Trying, in a sense, to reprogram the body. Pain is the fire alarm of a healthy, functioning nervous system. So the question becomes, can we make the mind aware that, yes, we’ve heard the alarm, we’re aware of the fire – but it’s a controlled burn, a regeneration burn, and therefore there’s no need to ring anymore. Can we tell it that? And will it listen?

“Ok,” Kirker says, “now start counting yourself down.”

I close my eyes and move slowly backwards from 50, breathing deeply, rhythmically. The idea is to slow down the brain activity and drift toward an alpha state, where the right brain, the creative, intuitive side, predominates.

“We’re going to just allow the body to numb,” Kirker says, “and we’re going to give the release to the teeth. We’re going to allow them to leave, and we’re going to allow the process to take place without invasion. The tissues will adapt if they need to, and healing will begin to take place as soon as the tooth is gone. We’re going to do the same visualization we’ve been doing, with the ice water, but we’re also going to draw our consciousness back from the body. To do that we’re going to go up some stairs in the mind. Only a few stairs until we reach a landing. Now look back and see your body in the chair.”

I can see it. The body. It’s me but it isn’t. It looks like an exhumed mariner from the Franklin Expedition, mummied in ice. The eyes are buried like bulbs under the skin, the whole left half of the face is crusted over with thick, white frost. This guy is dead.

Kirker reinforces the image with another. There’s a thermostat in the wall. The thermostat will be used to put the jaw into a deep freeze. At “1” the jaw is already numb. “When we turn the dial to the number 2, the numbness deepens, becomes more pervasive. Now turn the dial to 3. Turn it to 4. Deepening almost to the very tip of the root, now. Five. It’s starting to feel almost like stone. No sensation. Numb and very dense. You’ll still feel pressure, but nothing other than pressure.”

Image-making. In repressive regimes, the room where victims have been tortured has often been given a nickname. In the Philippines it has been called “the production room.” In South Vietnam “the cinema room.” In Chile “the blue-lit stage.” The very thing that manufactures and heightens sensations of pain – the projection booth of the mind – can be recruited to do propaganda for the good guys. In theory.

Somewhere across the room Cryderman is laughing. He and the receptionist strike up the Johnny Cash tune “Ring of Fire.”

I can hear things being unwrapped, instruments.

“Breathing in numbness,” Kirker says, “breathing out tension.”

A machine issuing three tones: GEG…GEG…

Cryderman is standing, for better leverage.

“Bruce is wired for sound,” he says, surveying the electrodes on my face.” “Second floor: lingerie.”

The top tooth is lying at an angle, like a newspaper box that’s been tipped over and frozen into a snowdrift. “It’s pointing a little sideways, but it’s manageable,” Cryderman says. His assistant, Monica, is at his flank. “I’m going to apply some pressure now around the upper wisdom tooth.”

You’ll feel pressure, but no pain.

Extracting a wisdom tooth is like prying an oyster off a rock. You’re pulling ligaments away from the bone, and attached to each ligament are nerves.

“Try and shift your lower jaw towards Monica,” Cryderman says. “Good for you.” The man is relaxed. He’s selling this. A little probing, a little digging – pressure, as promised, but pressure is not pain. Stone cold, bone numb.

“I’m going to try a straight elevator,” Cryderman says. “That was too easy.”

So far, so good. The dentist is smooth. He’s in there working on my mouth, and I haven’t really felt much of…

Mother of God.

Cryderman has leaned on the tool as if it were a tire iron. There’s a sick-making twisting, each sucker being yarded off the rock like snot till it pops free. Painwise, that was a six at least. Or was it? The lateral motion was what got to me, that unfamiliar sensation I interpreted as pain.

“You OK?” Cryderman says. “Yes? He’s going to be fine, then. You are going to be just fine.”

Pain is a private experience. To feel it even for a moment is to glimpse how it must, for chronic suffers, be a brutally estranging force. The human being is affiliative by nature, constantly reaching out; but the human being in pain is isolated, constantly looking in, drawing on reserves, spinning down to a hidden centre.

Quell the fear. Most of pain is fear. Breath in numbness, breathe out tension. Hey, this isn’t so bad. On the other hand, if the same procedure were happening in a different circumstance – the Tower of London in the 18th century, say – my subjective experience would likely be different.

“Hang in there, buddy,” Cryderman says. “Good show. So, we’re done there.” The top tooth is out. In seven minutes. Not exactly a slow float in the shallow end of the kidney pool, but manageable, surprisingly so. One down, one to go.

If I could somehow have known what was to follow, I might have bailed right there – paid up and been on the next plane home.

“I’m going to enlist your aid here, OK?” he says. “I want to control the bleeding in the lower left. I want you to imagine that the blood supply to that corner of your mouth is delivered by a garden hose. I want you to turn the tap off. Imagine yourself turning it right off. Cinch it down tight and shut the blood supply off to that wisdom tooth area. That’s it. Just imagine that you’ve stopped it altogether.”

Most of the tooth is covered by a crown of skin, which will have to go. Cryderman picks up a scalpel. Its blade is as long as my thumb.

“For all I know, this is the part that will bother you more than the actual tooth removal.” He pushes the blade in deep, drawing it down nearly a quarter of an inch and all the way forward, creating two flaps he then peels back on either side to expose the bone. It feels like a scraping, a scouring, a beating of rugs, uncomfortable for sure, but by now I have defined pain down – anything that doesn’t involve twisting is OK by me – and I let him go on.

“So we’re going to make some noise just like for a filling.”

Constant suction. Cryderman needs a point of leverage to get the tooth out of there. He starts to drill. Now he is digging a little trench in the bone. What helps stave off panic is that the drill, I discover, is preferable to the elevator, whose sudden, stump-uprooting action creates a more mentally vivid and therefore more flinchworthy sensation.

I can feel him moving back there. He’s a long way back, so far back that maybe he’s working on somebody else’s mouth. The mouth of the dead guy, Franklin’s man in the ice.

The tooth is butted up to the next molar too tightly. It’s not going to come out in one piece.

Cryderman starts to drill. He burrs down from the top of the tooth at an angle, the sound of a jet plane on takeoff heard through earmuffs. He brushes the pulp – a zing of pain, electric, a fist flying open. “Hang in there,” he says. “We’re making great headway.”

Whenever the rational mind is activated, there is suffering. Cryderman can tell when I am in my rational mind. He knows the circuit is open, two people receiving each other. He’s talking to me now, engaging directly. He knows I’ve gotten off the lift and am taking the stairs, and he is helping me up those stairs.

I fall back on the Jose Silva technique. The trick, Silva figured, is to concretize the pain, make it a physical thing. The right brain, which creates pain sensations, deals with subjective constructions. It can’t deal with things. So once you’ve given pain dimensions, you’ve taken it out of the right brain and put it into the left, which feels nothing. Concretize the pain. It is the shape of the sun, the sudden weight of a wheelbarrow full of rocks.

“Thanks for opening so wide,” Cryderman says. “I had a little girl just before you, and I keep wanting to say, ‘Bruce is being a big helper.’”

With a loud crack the corner of the tooth shears off. The idea is to plug the elevator in and try to level the tooth out. But again, it refuses to budge.

Strategy changes. Cryderman and his assistant have a little conference. Kirker, who has been down at my feet massaging the acupressure points, pops up to have a look. “OK, let’s try it,” Cryderman says finally. “We’ll just go really slow and see how we do.” He begins to drill straight down into the pulp chamber of the tooth. If lidocaine were ever going to be needed, it’s now. I can feel the burr going in, but the pain is more a frisson than a jolt, no worse than some of the bad dentistry I had as a kid, nothing I can’t handle. If the other “pain” sense cues were absent – the scraping of the scalpel, the cracking of the teeth, the smell of burning pulp – there would be almost no sensation. At intervals Cryderman stops drilling and tries levering. I can hear myself making whale sounds. “Let’s give him a rubber bite-block – that should improve his ability to stabilize his own jaw,” Cryderman says. “I think that’s going to help you, Bruce, because I’m torquin’ on ya.”

The roots of the tooth have grown together into a kind of monoroot, which means Cryderman will have to bore down almost all the way down to the jawbone before the tooth splits. Then all that will remain is to slip an elevator into the crack, twist it, and the two pieces should split like cordwood, free to be lifted out. In theory.

Light blooms periodically as Cryderman’s headlamp beam passes over my eyelids. I can feel tight skin near my temples where the tracks of tears have dried.

The steady trickle of the waterfall. Kirker has turned up the current on the electrodes on my face so I will feel a reassuring buzz, but I don’t feel a thing.

A hazy notion is born and forms and tries to take hold. It’s the sense that there are two worlds in opposition – the world I normally live in, the grasping world, self-centred and busy and messy, my brain full of way too much pop-cultural arcana; and the other world I am beginning to glimpse, a letting-go world, a place of acceptance and submission and yes, faith, where the real show is happening beyond conscious awareness, your biochemistry sensitive to toxins at almost an atomic level, dead relatives along with you for the ride and every organic thing pulsing at an almost audible frequency, giving off a visible light. A place that, once you decided to live in it permanently, would probably make the other world look like the restroom of a gas station next to the beach.

How we experience pain, eventually, falls into the preverbal realm, or possibly postverbal – casting us back into the frustrating limitations of infanthood or forward to the final mumblings in the vapour tent before the ventilator is turned off. English has no words for it. At best our descriptions are crude approximations. Pain is the original language, not what the body speaks to the world but what the world speaks to the body: you are still alive.

Cryderman is almost entirely through the tooth. “Hang on,” he says. “I think I’m going to have some good news for you pretty quickly.”

The tooth splits with a crack. “OK, let’s see what we’ve got.” The two pieces should lift out easily. But they don’t. They are fused to the bone. Akylosis. Cryderman will have to pry each out individually.

At this point let me collapse the story. Plenty of things happen in my mouth, and plenty of things happen in my mind, not least of which is that I adopt a new strategy, leaning not on images, but on fact (“Look, this is the way it was done for thousands of years”) and affirmations (“The only way out is through”). Cryderman describes a required manoeuvre to Monica as a “dipsy-doodle.” He tells her to be a little more aggressive. At a certain point, I find myself talking to the tooth: “Let go, pal.” The tooth and I have fairly clear communication going. We are staring at each other across the table of a bad Mexican restaurant on the night, after 25 years together, that it all ends. The tooth says, “Why are you doing this to me? What have I ever done to you?” It senses an impure motive. This is not a diseased tooth. It wasn’t causing any trouble. Strictly speaking it did not need to come out. Was the thrill gone? Was there another, younger tooth in the picture? No. I was doing this for the money.

“OK, Bruce,” Cryderman says. “You made it.”

Sixty-five minutes after he began to tackle it, the last piece of this tooth is out. Cryderman’s face is filmed with sweat. “Holy mackerel,” he says. He puts a couple of stitches in. I don’t feel them. I am floating on endorphins.

This has turned out to be one of the most stubborn extractions Cryderman has ever undertaken.

“OK, I’m not ordering anything with sun-dried tomatoes on it this weekend,” Cryderman says “Monica is destroyed on sun-dried tomatoes now. Possibly forever.”

In his byzantine excavations, Cryderman managed to miss the major nerve that runs under the wisdom teeth – if he’d hit it I doubt any amount of acupuncture or guided imagery would have prevented me from jumping out of the chair. But even so, this was a pretty sensational bit of trauma. And with acupressure, and what amounts to positive thinking, I was able to endure it. the dissociation from my own body in the chair – not “astral travel,” but something closer to a state of light hypnosis, suggestibility with awareness – worked. “Turning off the tap” worked. Cryderman removed only two gauzes’ worth of blood – way less than there should have been for a wound that size. A dental patient who’s not completely frozen will typically feel pain the moment the drill penetrates the enamel, moves into the dentin and brushes the pulp. Cryderman drilled right through the pulp. “That,” says Kirker, “is like doing surgery.”

Here’s the truth. I am not a tough guy. I cry at track meets. And I’m easily distracted. A stronger person with a more disciplined mind could almost certainly enjoy something close to a pain-free experience.

“Western medicines definitely have their place,” Kirker says as we make our way back to the IMI in his minivan. “They’re very useful for some things. It’s hard to beat a good nerve block.” I know what he means. Strictly in terms of quantifiable pain, the Western side of this experiment “won” hands-down. But the Eastern side was a lot more interesting.

No doubt Silva made some mistakes, and Iris misses the barn some days, and Deepak Chopra bends some facts to fit his myths, and a lot of the “Kirlian photography” people you see at science fairs are charlatans, waving the Polaroid over a 60-watt bulf before handing you back an aureole-ringed picture of yourself. But somewhere in the fog is the right way forward – to a future where doctors are paid even if they don’t make a referral or prescribe a pill, and patients are encouraged to do all they can for themselves, and Western and Eastern medicine collapse into something we call ‘using what works.’ And pain still exists though we all start thinking about if differently, trying to answer the question of why it dogs us from a little further upstream.

The healing curve on this left side is steep. Kirker gives me a couple more sessions of the oxygen and the lights. He makes a liquid homeopathic out of the pieces of my own tooth. He feeds into the bioresonance machine he’s using on me the signature of healthy tissues from pigs raised on an organic farm in Germany. (Using healthy human flesh would no doubt present, um, ethical issues.) There is very little swelling, which surprises him. “When you touch bone,” he says, “almost invariably you swell up like a chipmunk.”

The night of the operation there’s a little low pain, maybe a Two, not enough to prevent me from sleeping. The next morning it is gone.

On Monday, Kirker and I shake hands goodbye.

“Oh. Iris phoned,” he says. “I asked her if she was there. ‘Oh yeah,’ she said. ‘Dragged on awhile, eh?’”